A brilliant, absurdist Brontesque thriller

By Tania Herbert

Haze cascades down from the ceiling, and the severe form of a Victorian woman is lit to look like a cameo brooch. Thus opens The Moors at Red Stitch Theatre, and I already have a little thrill of expectation.

Wandering into the tiny, immaculate theatre of Red Stitch is always an expected delight. What was less expected though, was this gothic surrealist gem of a play by Jen Silverman.

Governess Emilie (Zoe Boesen) is lured to a new job at a manor on the moors, after an exchange of sultry emails with the lord of the manor. She arrives to find that there appears to be no child, her bedroom looks suspiciously like the parlour, and her benefactor is nowhere to be found.

Instead she quickly finds herself embroiled in the mysteries of the household, with the multiple personalities of the housemaid (Grace Lowry), melancholies of tortured writer Hudley (Anna McCarthy) and the chilling powers of Agatha (Alex Aldrich), the formidable sister of the missing lord.

The gothic thriller set-up is counterpointed by the parallel story of the depressed family hound who forms an implausible relationship with a damaged moor-hen unable to fly away (played by ensemble actors Dion Mills and Olga Makeeva).

The set-up and absurdist nature of the play could have easily ended up out of hand, but was held in place by extremely tight direction under Stephen Nicolazzo, and particularly the strength of characterisation by all cast members. For every performance, the simmering darkness within was captured, presenting a gripping two hours of theatre. With an almost all-female cast, the play pushed gender roles in particularly interesting ways – my feeling was that the play isn’t foregrounding a feminist message as such – but rather, is a story with an exceptionally strong cast of characters and actors – most of whom happen to be women.

It is difficult to highlight a particular standout performer, as every cast member was strong, convincing and compelling. Perhaps my personal favourite was Olga Makeeva mastering the challenge of playing both an anthropomorphised bird, but also the relative ‘everyman’ against the absurdities around her.

The accent variation grated on me a little, as Australian ocker just doesn’t seem congruent with the English moors, but given the surrealist nature of the work, this did not subtract overall. This play won’t be for everyone – it is dark in mood, appearance and humour with horror elements and a bit of lustiness.

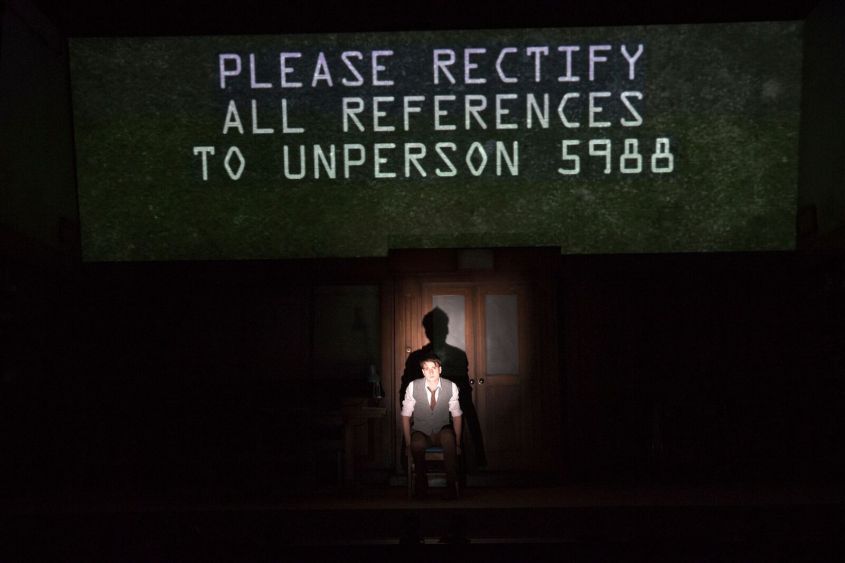

Sinister, dark, and humorous, watching The Moors feels like peering into a gothic dollhouse of horrors.

The Moors is performing at Red Stitch Theatre, Rear 2 Chapel St, St Kilda East

Dates: 6 June- 9 July, Tuesday-Saturday 8pm, Sunday 6.30pm (Post-show Q&A 22 June)

Tickets: $15-$49

Bookings: (03) 9533 8083 or www.redstitch.net

Image by Jodie Hutchinson